Alain Satié — Artist and Friend: An Appreciation

by David W. Seaman

Saint-Germain-des-Prés is the home town of the avant-garde in France, and especially of lettrism. Saint Germain is where Isidore Isou settled in the 1940s and where he remained until his death in 2005. In his 1951 film, Traité de bave et d’éternité, Isou is seen wandering around Saint Germain, and that is where Orson Welles interviewed Isou and Maurice Lemaître for his BBC series, Around the World with Orson Welles. Saint Germain is put on the map of the universe by Lemaître in his hypergraphic work, Canailles, and it is parodied by Gabriel Pomerand in his hypergraphic novel Saint-Ghetto des Prêts.

According to the Lettrisme internationale authors of Visages de l’avant-garde (1953), which Jean-Paul Rocher just published in 2010, Isidore Isou had set up his headquarters at the Café Bonaparte, in sight of the Eglise de Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and daily gave instructions to his lieutenants Lemaître and Pomerand.

Alain Satié was living in Saint Germain when I first met him. We got together at a cafe, and later went up to his studio/apartment. Over the years we met at his place in the Poissonnière neighborhood, and then especially out at his remodeled farmhouse in the village of Bouleurs, near Meaux.

My first look around Satié’s studio made an impact that was renewed every time I visited him: here was a whole gallery of work centered on certain principles -- the basic tenets of lettrism, which Satié happily explained to me -- and yet widely ranging in expression and style. For instance there was Satié’s elaboration of the three words, "lettre, mot, signe." He did them in folded newspapers, molded in plastic, mowed into an acre of grass, and eventually in a wisteria vine that he laboriously guided into the shape of the word "lettre." Several attempts were required before the eventual success, which I recorded in the film, "Alain Satié and the Meta-esthetics of Wisteria."

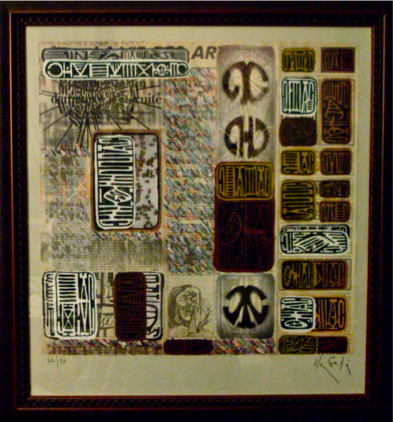

About this time I began collecting Satié works, the first one being a complex piece where the "canvas" was a page from an art newspaper, that Satié had covered with a rich variety of his signs and cartouches. This is what lettrists call a chiseling work, destroying the previous canon (an image of a Picasso work is left showing on the arts newspaper), while I find it is also an amplifying work, enriching the imagery with new signs.

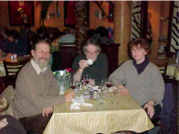

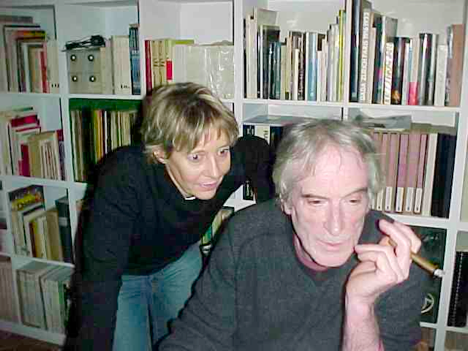

Another Satié project was to transform locations into lettrist works by including a card on which he had made a lettrist design that included the letters "PIPE." He would then photograph the scene, such as the Red Square in Moscow, and label it as a lettrist work (not unlike a wolf marking his territory with urine). This practice was extended to alligators in the only collaborative piece he and I did. Satié had revealed his fascination with alligators when we went to dinner at Disneyland Paris, not far from his rural home. Satié enjoyed the American veneer of the hotel bars and the restaurants located near the park, and we would go there to have dinner or a drink. This photo shows me with Satié and his long-time partner the lettrist artist Woodie Roehmer at Planet Hollywood.

Another Satié project was to transform locations into lettrist works by including a card on which he had made a lettrist design that included the letters "PIPE." He would then photograph the scene, such as the Red Square in Moscow, and label it as a lettrist work (not unlike a wolf marking his territory with urine). This practice was extended to alligators in the only collaborative piece he and I did. Satié had revealed his fascination with alligators when we went to dinner at Disneyland Paris, not far from his rural home. Satié enjoyed the American veneer of the hotel bars and the restaurants located near the park, and we would go there to have dinner or a drink. This photo shows me with Satié and his long-time partner the lettrist artist Woodie Roehmer at Planet Hollywood.

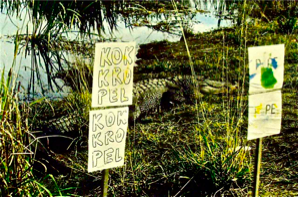

One place Satié liked in particular was a restaurant which had a fake jungle including an animatronic alligator that would rise up and open its jaws. So when Satié came to visit in south Georgia, he wanted to see alligators in the wild. Unfortunately, it was January, and the beasts are mostly hiding in the mud at that time. But he explained his intentions, and when the alligators came out to sun themselves later that summer, I carefully approached and planted his card and my own beside the somnolent beast, turning the swamp into a lettrist landscape.

The farmhouse in Bouleurs where Satié had made his permanent home and studio became my Parisian home base, where I would visit Satié whenever I came to France. The home itself was a gallery, with examples of all stages of Satié’s work, from the carved wood dining set to the illuminated wall designs. A three-story barn was converted into a billiard room hung with the series of flags that Satié had created for the bi-centennial of the French revolution in 1989 and had hung over the streets of Saint Germain; one of his sculpted chairs can be seen in the corner. He brought these flags to Georgia when he came in 2000 and we hung them across the atrium of the university union.

The farmhouse in Bouleurs where Satié had made his permanent home and studio became my Parisian home base, where I would visit Satié whenever I came to France. The home itself was a gallery, with examples of all stages of Satié’s work, from the carved wood dining set to the illuminated wall designs. A three-story barn was converted into a billiard room hung with the series of flags that Satié had created for the bi-centennial of the French revolution in 1989 and had hung over the streets of Saint Germain; one of his sculpted chairs can be seen in the corner. He brought these flags to Georgia when he came in 2000 and we hung them across the atrium of the university union.

Satié welcomed me and my wife Barbara at Bouleurs. Barbara did not especially care for the long walk from the bedroom to the bathroom, but was mollified when one morning she passed Satié’s son Julien on the way, and he later remarked that a "goddess had walked by." Satié also tried to please us with his cooking. He served his delicious signature dish, poulet aux olives, where he forced green olives under the skin of the chicken which sizzled on the rotisserie, its drippings flavoring the potatoes below.

Satié welcomed me and my wife Barbara at Bouleurs. Barbara did not especially care for the long walk from the bedroom to the bathroom, but was mollified when one morning she passed Satié’s son Julien on the way, and he later remarked that a "goddess had walked by." Satié also tried to please us with his cooking. He served his delicious signature dish, poulet aux olives, where he forced green olives under the skin of the chicken which sizzled on the rotisserie, its drippings flavoring the potatoes below.

Not all culinary efforts were successful, though. One time as he drove us up from the train station in Crécy to Bouleurs, he turned to Barbara and enquired in English, "you like upstairs?" Barbara puzzled this one over for a minute; usually we had an upstairs guest room ... Satié looked to me for help: "les huîtres, c’est quoi?" "Oysters!" I splurted. "Oh, merde," said Satié, and that was the end of his English-speaking. But the oysters were excellent.

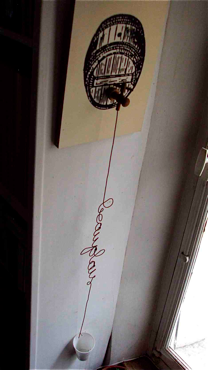

Elsewhere in the house were Satié’s extensive library of lettrist works, and a large work table. He did most of his graphic work in the studio, but also had a workshop in an outbuilding where he did more robust physical pieces. In every corner there were works of lettrist art, such as his whimsical homage to Beaujolais wine in a wire sculpture hanging alongside a window.

During this stage of our relationship Satié made sure I was invited to the lettrist group shows, and sometimes I came to France to attend the opening and finish up framing my works in Satié’s workshop. I had to learn a special French word for tacks used to attach canvas, not clou but semence.

During this stage of our relationship Satié made sure I was invited to the lettrist group shows, and sometimes I came to France to attend the opening and finish up framing my works in Satié’s workshop. I had to learn a special French word for tacks used to attach canvas, not clou but semence.

One show I joined was at the Galerie Visconti, in the rue Visconti in the Saint Germain district. In that show I presented two of my petroglyph series. Satié had encouraged me to find my own personal series of signs, just as he had developed a characteristic swirling series that he sometimes referred to as "my signs." He had apparently created a set of stencils that he could use to apply his signs to any works he was doing. Other lettrists had their own recognizable "alphabets," developed after Isou had asserted that hypegraphics allowed lettrist artists to use all available alphabets from any language or culture, as well as invented ones. Thus Broutin was inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphics, Poyet seemed to have Chinese inspiration, and so forth. As the only American in the group, I turned to American Indian sources and studied the petroglyphs and pictograms of the American southwest to find a language of signs.

I was also invited to join in the monthly lettrist meetings. These occurred on the last Thursday of the month, so it was not always easy to connect. The first time I went was in the back room of a little café located near Place de la République. This one had been chosen because it was in no one’s neighborhood, so it avoided everyone’s turf. We had a simple dinner and discussed upcoming events and shows. I had expected sharing of ideas and works, but that was not what they did. It was more like a business meeting. When I was filming interviews I distributed permission forms at the meeting; some asked me about author’s rights and fees. As a scholar, I insisted it was all non-profit.

I was also invited to join in the monthly lettrist meetings. These occurred on the last Thursday of the month, so it was not always easy to connect. The first time I went was in the back room of a little café located near Place de la République. This one had been chosen because it was in no one’s neighborhood, so it avoided everyone’s turf. We had a simple dinner and discussed upcoming events and shows. I had expected sharing of ideas and works, but that was not what they did. It was more like a business meeting. When I was filming interviews I distributed permission forms at the meeting; some asked me about author’s rights and fees. As a scholar, I insisted it was all non-profit.

Later we met at the more upscale Café Français at the Place de la Bastille. This was an after dinner meeting, so Alain and I would get together at a Belgian mussels chain, and have moules à la crème before the meeting. The last one I went to was attended by my favorite lettrists, Broutin and Poyet, who had been in high school together and entered lettrism as young rebels, Woodie Roehmer, still elegant, Sabatier and Anne-Catherine Caron who had returned to the movement (from Italy) and of course Satié.

My own collection of Satié works was growing, and a favorite work is a relief sculpture that seems to say "smile." This is exquisitely Satié, with his recognizable arabesques and also some letters and combined alphabetic forms. This 1989 work is a compact version of what would become a series of ever larger relief works that eventually included hidden lighting.

Other features of the house in Bouleurs were the dog and the cat. Doune the dog was a wonderful companion and marvelously trained. We took walks through the village with no leash, and when we went to the grocery store in nearby Crécy, Doune would sit patiently with the buggies at the front of the store until we came out. Satié encouraged Doune to chase the ducks in the river, and enjoyed her efforts to enter the cat door. When Satié died, Doune remained at the gate, waiting for her master to come home.

Other features of the house in Bouleurs were the dog and the cat. Doune the dog was a wonderful companion and marvelously trained. We took walks through the village with no leash, and when we went to the grocery store in nearby Crécy, Doune would sit patiently with the buggies at the front of the store until we came out. Satié encouraged Doune to chase the ducks in the river, and enjoyed her efforts to enter the cat door. When Satié died, Doune remained at the gate, waiting for her master to come home.

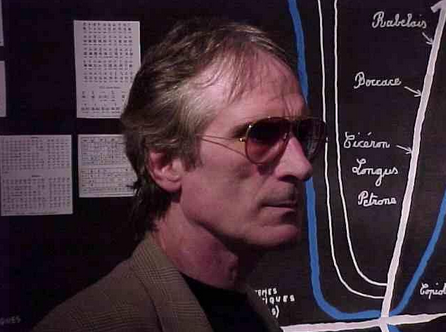

The trip to the United States in 2000 coincided with a major exhibition of lettrism and its historical significance that I had created at Georgia Southern University. Several lettrists contributed large paintings, and I gathered artifacts from cuneiform scrolls to Arabic calligraphy to place the works in context. A major piece was the synoptic work referred to as Sabatier’s "schema." This huge painting/collage was a version of what the lettrists had shown at the Venice biennale, and it was basically an illustrated time-line of the development of painting and writing from the very beginning up to the lettrists. Roland Sabatier, the creator, is the older brother of Satié, and he plays the role of historian and theorist for the movement, authoring an important study, Le Lettrisme – les creations et les créateurs (Z’Editions, s.d). Because of the prominence of his brother, Alain Sabatier changed his artist name to Satié. This photo shows Satié at the exhibition, "From Letters to Lettrisme," in front of the "schema."

The trip to the United States in 2000 coincided with a major exhibition of lettrism and its historical significance that I had created at Georgia Southern University. Several lettrists contributed large paintings, and I gathered artifacts from cuneiform scrolls to Arabic calligraphy to place the works in context. A major piece was the synoptic work referred to as Sabatier’s "schema." This huge painting/collage was a version of what the lettrists had shown at the Venice biennale, and it was basically an illustrated time-line of the development of painting and writing from the very beginning up to the lettrists. Roland Sabatier, the creator, is the older brother of Satié, and he plays the role of historian and theorist for the movement, authoring an important study, Le Lettrisme – les creations et les créateurs (Z’Editions, s.d). Because of the prominence of his brother, Alain Sabatier changed his artist name to Satié. This photo shows Satié at the exhibition, "From Letters to Lettrisme," in front of the "schema."

Satié’s own work in the show was a large canvas devoted to Lafayette, the Frenchman who had helped the United States fight off the British, and who had later returned to south Georgia to eat alligator, go to parties, and make speeches.

Woodie Roehmer accompanied Satié to the United States in 2000, and she contributed a floating sculpture that was launched in a special event. Her playful style always added lighter charm to the lettrist exhibitions, and in spite of her nervousness about riding in the canoe, her sculpture was a successful addition.

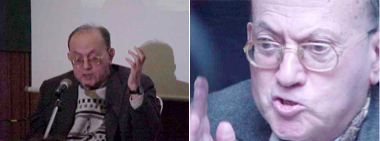

Satié made sure that I completed my involvement with lettrism by taking me to visit Isidore Isou in his tiny lodgings, still in the heart of Saint Germain. By this time, Isou was ill with a disease that affected his balance, so he stayed in a restricted space between bed and chair. He was also difficult to understand, but his mind was alert and he knew who I was, had read my articles, and gave me advice on promoting lettrism. He was still the intellectual force behind lettrism, but no longer the handsome young revolutionary seen strutting around Saint Germain in his movie. Isou made one last public appearance at an event at the Sorbonne in October 2000, speaking in a voice that trembled into a semblance of his early lettrist poems.

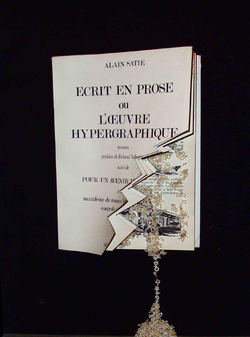

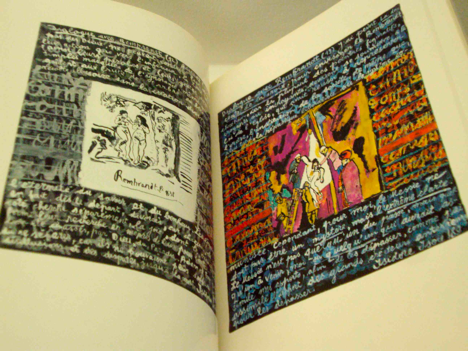

Among the many forms of lettrist work, the hypergraphic novel is one that stands out for its inventiveness. It essentially takes the narrative and puts it into visual form, and the result looks like a "bande dessiné," the famous French comic books, but with hypergraphic texts in the place of the usual speech bubbles. This strain of lettrism began with Isou’s Journaux des Dieux, continued with Pomerand’s Saint-Ghetto des Prêts and Lemaître’s Canailles. Sabatier contributed Gaffe au Golfe, and Satié created Ecrit en prose. This latter work was also presented as a sculpture, where the letters are seen streaming out of the book.

Among the many forms of lettrist work, the hypergraphic novel is one that stands out for its inventiveness. It essentially takes the narrative and puts it into visual form, and the result looks like a "bande dessiné," the famous French comic books, but with hypergraphic texts in the place of the usual speech bubbles. This strain of lettrism began with Isou’s Journaux des Dieux, continued with Pomerand’s Saint-Ghetto des Prêts and Lemaître’s Canailles. Sabatier contributed Gaffe au Golfe, and Satié created Ecrit en prose. This latter work was also presented as a sculpture, where the letters are seen streaming out of the book.

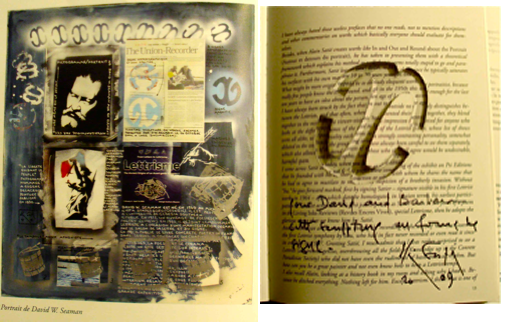

In recent years, Satié turned more often to theoretical writings, and I collaborated as his translator. Sometimes this was to produce pieces for Kaldron’s Lettrist Pages on the internet, and sometimes it resulted in bi-lingual editions, such as the book, Autour et détours du portrait / In and out and roundabout the portrait, published in Verona by the great Italian patron of the avant-garde, Francesco Conz, in 2009. After the theoretical discussion, the book includes Satié’s lettrist portraits of Broutin, Anne-Catherine Caron, Jean-Pierre Gillard, Micheline Hachette, Isidore Isou, Maurice Lemaître, Gabriel Pomerand, François Poyet, Woodie Roehmer, Roland Sabatier, Alain Satié, David W. Seaman. It is an unselfish homage to the lettrists who connected with Satié throughout his career. In typical fashion, Satié made his dedication to Barbara and me into a three-dimensional work.

Satié also dedicated one of his "sliced book" works to Barbara as a birthday gift. He attached a note suggesting that she was in evolution in the same way as this "infinitesimal" work. In lettrist parlance, that means it is a work with an infinite number of meanings, based on the interpretations and interactions of viewers. In this case, the "white pages" of the phone books can also be called "blank pages," leaving the reality wide open.

Satié was often involved in memorializing and contextualizing his lettrist colleagues. One time he asked me for a photo of Barbara and me, along with some text of mine. I sent him a beach photo and a linear poem about eating smoked salmon and smoking, called "Smoky Kisses." In return, he offered us one of his "dihedral" works, where the two elements I provided are combined with Satié’s signs in a relief sculpture.

Satié’s companion in his later years was Isabelle Ganne Caron, whose sister had had a long off and on relationship with the movement. Isabelle is not an artist, but she expressed an extremely fine understanding of the meaning of being lettrist, and she admired Satié’s devotion to his artistic calling. I found her to be an affectionate and supportive companion for Satié, and we spent many happy times together. This included following Satié on some of his long walks through muddy fields, then long evenings with discussion and his inevitable urging to me to write a book about lettrism. Isabelle would drink tea and infusions while Satié and I shared some scotch. It also included Satié’s macho stupidity, such as not wearing a seatbelt, or not using windshield wipers in a snow storm. (Isabelle would just reach over and turn them on.)

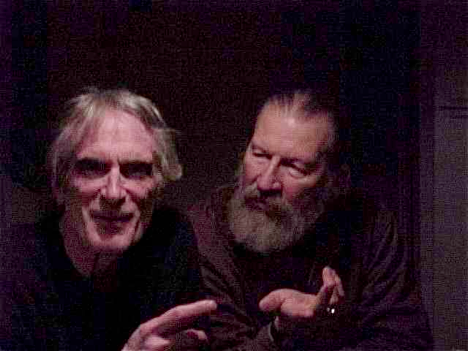

During one visit Satié had a new camera, and we played with photos that we could quickly load onto the computer to view and manipulate. Isabelle became the photographer for a series of photos that included this shot of Satié and me in chiaroscuro, pretending to be Dutch masters.

It is difficult for me to end this discussion of Alain Satié; my own art and vocation are tied to my relation with Satié, both positively and negatively. We agreed on much, but differed too, and I am still seeking the balanced way beyond his presence. This is not the place to reveal our many tastes and distastes, but finally I just miss him as a friend. The art world will read the book I will eventually write, and then everyone will also see Satié as an important artist. Some have suggested that an artistic revolution has run its course when its works are enshrined in books and museums. During a visit to Paris in June, 2011, my students excitedly reported that they had seen lettrism in the Centre national d'art et de culture Georges Pompidou. I went to Beaubourg to see for myself, and indeed there were two vitrines with newly acquired lettrist works, including paintings, books and objects. Among them was this book by Isou, still looking fresh and engaging. It reminded me of the spirit of Alain Satié, always creating, always at the avant-garde of the avant-garde.

SCRIPTjr.nl

SCRIPTjr.nl